In the sprawling necropolis of Wadi Al-Salam in Najaf, south of Baghdad, grave diggers whisper tales of a terrifying creature known only as “Al-Tantala”. More than just folklore, this entity is said to stalk the vast cemetery, inflicting fear and even physical harm upon those who work amidst the endless rows of graves. Is it a figment of traumatized imaginations, or a chilling reality lurking within the silent city of the dead?

Wadi Al-Salam: A City of Souls

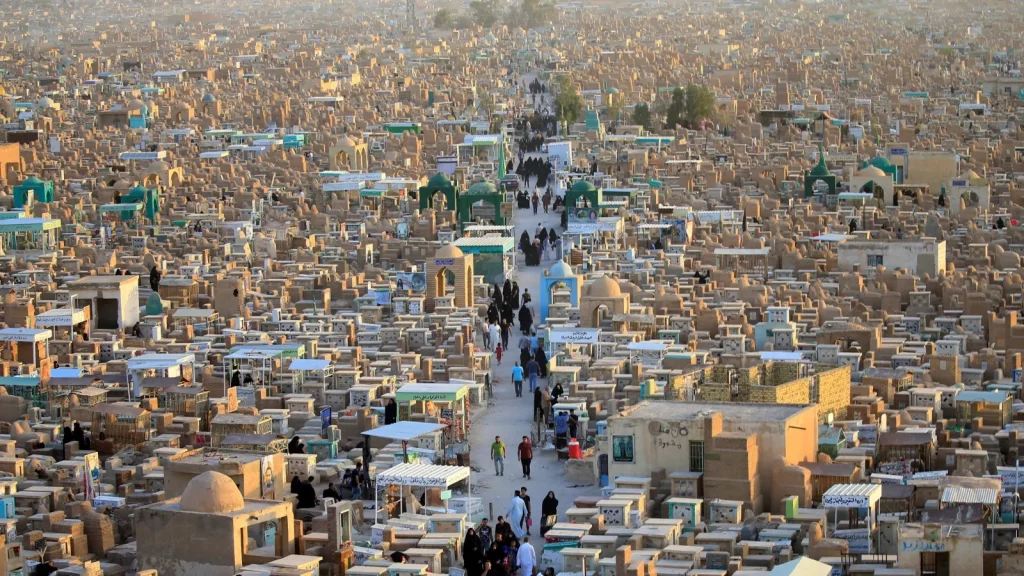

Often described as the world’s largest cemetery, Wadi Al-Salam spans six square kilometers, a silent metropolis within the holy city of Najaf, 200 kilometers south of Baghdad. For nearly 1,500 years, this sacred ground has been a final resting place for millions, drawing thousands of Shia pilgrims annually. Yet, this profound silence has been shattered by the unsettling legend of Al-Tantala, a elusive and frightening presence that has left grave diggers questioning their sanity and safety.

The emergence of such a chilling tale in Wadi Al-Salam is deeply intertwined with Iraq’s contemporary reality. Since 2003, the nation has buried approximately 207,000 civilians, a grim annual average of 13,000 lives lost to conflict and bombings. Wadi Al-Salam, which holds an estimated five million souls, inters around 50,000 bodies annually – over 4,000 per month. During the war against ISIS (2014-2017), gravediggers in Najaf were burying up to 100 fallen soldiers daily, each earning a meager 300-400 euros a month for their perilous work.

Encounters with the Unknown: Tales of Al-Tantala

Hani Abu Ghunaim, a 61-year-old gravedigger, speaks with a chilling certainty: “There are two types of living beings: people and the Tantala, which comes out at night and takes various forms.” Other workers recount the mysterious deaths of four colleagues in 2018 under suspicious circumstances while on duty.

Haider, another gravedigger, vividly recalls an encounter in December 2016. While digging a grave, he saw a shadow in his peripheral vision before a powerful blow knocked him unconscious into the pit. “The phantom invaded my body, starting from my head before spreading throughout,” he recounted. “When it left, I fell immediately. After that, I felt convulsions in my jaw, like paralysis, and then I lost consciousness.”

The psychological toll of these encounters is immense. A veiled woman recounted her son’s ordeal after an alleged encounter with Al-Tantala. “My son lost everything – his job, his wife… He has no money to buy milk for his children or pay his rent.” Medical scans showed no signs of a stroke, yet confirmed a severe impact requiring medical intervention. His mother lamented, “The Tantala cost us thirty thousand dollars for my son’s treatment, and he consulted many religious figures to help him get rid of this monster that still inhabits his body.” Her son still feels the entity in the right side of his brain, plagued by pain and nightmares. His father firmly stated, “After this incident, we will not allow him to return to work in the cemetery again, or we will lose him permanently.” The son echoed this fear: “I truly cannot go back to the cemetery because I am afraid that this monster will end my life. Being a grave digger has become a dangerous profession.”

The Stigma of Mental Health in Iraq

Despite their profound trauma, individuals like Haider often avoid seeking professional psychological help. In Iraq, mental illness carries a significant stigma, with 65% of Iraqis viewing it as a sign of “weakness.”

Murtada Jawad, another gravedigger, shares an equally unsettling experience. At dawn, while preparing to place a woman’s body in her grave, he felt a slap from her bound hands. “I don’t know how that happened when her hands were tied under the shroud. It still terrifies me.” Convinced that the entity possessed the woman’s body to threaten him, Murtada felt paralyzed that night but dared not scream, fearing the deceased’s family would think him mad. Alone, he succumbed to his fears of Al-Tantala, haunted by the possibility of losing his mind. Showing numerous small scars on his arm, Murtada admitted, “I have often burned my arm with cigarettes. I tried to commit suicide several times, but my mother intervened each time to save me.”

Like Haider, Murtada became isolated, accused by friends of fabricating stories and deemed mentally unstable by others. Many gravediggers, witnessing similar inexplicable phenomena, simply abandon the profession, unable to psychologically withstand the experiences.

Overcoming Fear: A Path to Healing

The profession of grave digging in Murtada’s family is passed from father to son, a tradition now threatened by his harrowing experience. His father recalled warnings from his own father and uncle about strange incidents before he began working. Murtada, who has been immersed in the world of the dead since age ten, had no issue with seeing bodies.

After a five-year hiatus, Murtada will resume his family’s tradition. He spent this time in an American psychiatric hospital in Lebanon, a journey that cost $7,000. “I will not be afraid anymore,” he declared. “The doctor helped me get rid of my depression, and of this memory and my fears associated with it.” He has since married, after obtaining a medical certificate proving his sound mental health. Regarding Al-Tantala, he asserts, “Thank God, I have greater faith today. I have no choice; I must keep moving forward for my family.”

Murtada’s need to seek treatment abroad highlights a critical issue: Iraq’s severe shortage of mental health care. According to Doctors Without Borders, as of 2012, there were only four psychologists per million people in Iraq, and the provision of care remains catastrophic. Ahmed Khaled, head of an emergency department, is pessimistic about the victims of Al-Tantala, stating, “The population generally has a bad idea about mental illnesses and lacks sufficient knowledge. A patient seeking care risks falling victim to social stigma.”

Despite the skepticism, Hani Abu Ghunaim offers a unique perspective. Guiding visitors through the most expensive part of the cemetery, below the Shrine of Imam Ali, he opens a small crypt entrance, descends into the deep darkness, and lights candles, revealing a bald, mustached man in a tie. Hani confidently asserts he has seen Al-Tantala many times in his 11 years of grave digging, even advising younger workers on how to cope. He then goes to collect water from the Najaf Sea. “I spray them with the liquid to heal their wounds,” he says, “and they must also drink a little of it.”

The Economic Heartbeat of Najaf

Beyond the chilling tales, Geraldine Chatelard, a researcher at the French Institute for the Near East, emphasizes the cemetery’s profound importance: “Najaf would not exist without the cemetery.” It is the city’s economic lifeline. She insists that the “professions of death” are not marginal but “the heart of Najaf’s economy and its social organization.” Yet, this normalization of death does not prevent the marginalization of gravediggers, especially those haunted by Al-Tantala.