For millennia, the colossal pyramids of Giza have stood as silent sentinels on the Egyptian plateau, their imposing presence near the Nile River sparking countless theories about their purpose and construction. From the macabre tales of Herodotus to fanciful medieval interpretations and modern-day esoteric claims, the true function of these ancient marvels has been shrouded in speculation. Yet, despite the wild conjectures, the prevailing and most substantiated theory, held by Egyptologists then and now, remains that the pyramids were tombs for pharaohs.

Ancient Narratives and the Tomb Theory

As early as 450 BCE, the Greek historian Herodotus recounted a rather scandalous tale involving the pharaoh Khufu and his daughter, suggesting an unconventional origin for one of the pyramids. While his narrative paints a picture of royal desperation and an ingenious daughter using stones from her “clients” to build a pyramid, even Herodotus acknowledged the more widely accepted belief: these structures were royal burial sites.

Modern Egyptology overwhelmingly supports this conclusion, and for good reason. The pyramids are strategically located on the western bank of the Nile, a side deeply intertwined with the setting sun and the journey to the afterlife in ancient Egyptian mythology. Archaeological digs around the pyramids have unearthed ceremonial funerary boats, believed to be vessels for the pharaohs’ voyage to the next world, along with numerous other tombs belonging to members of the royal court.

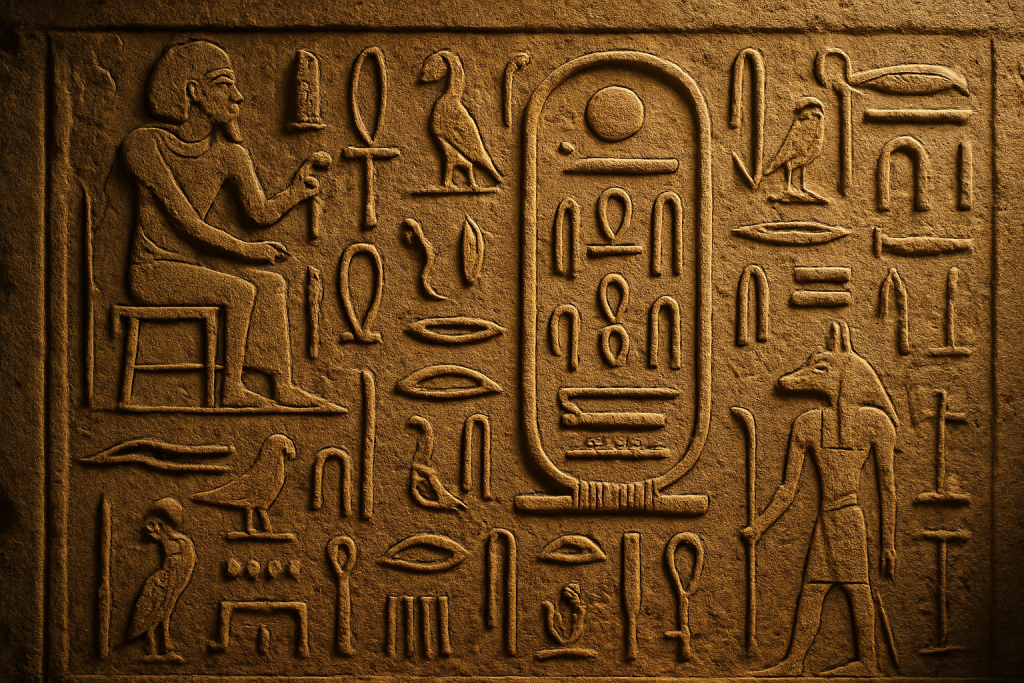

Perhaps the most compelling evidence lies within the pyramids themselves. Many contain stone sarcophagi or coffins. By the 19th century, hieroglyphic inscriptions found on or near these sarcophagi were identified as magical spells, intended to guide the pharaohs through the transition to the afterlife.

The Confounding Absence of Bodies

However, a crucial piece of the tomb theory has historically been missing: the pharaohs’ bodies. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, explorers and archaeologists meticulously investigated over eighty pyramids across Egypt. Time and again, they opened what appeared to be royal sarcophagi, only to find them empty.

The most common explanation for these vacant tombs is looting. Ancient and even later thieves were primarily interested in the pharaohs’ immense treasures, not their remains. It’s improbable they would have spent significant time ensuring the proper preservation of bodies, nor would they have left behind mummies adorned with pure gold.

Early grave robbers were likely ancient Egyptians themselves, as evidenced by the elaborate and often futile anti-theft measures incorporated into pyramid design. The pyramid of Amenemhat III at Hawara, for instance, features a labyrinthine series of false passages, hidden doors, and massive stone blocks designed to deter intruders. Yet, these ingenious efforts ultimately failed, as attested by accounts from later treasure hunters like the 9th-century Arab governor Abdullah al-Mamun, who reported finding only an empty sarcophagus in Khufu’s Great Pyramid.

Later European explorers, like Giovanni Belzoni in 1818, were no less destructive. Using battering rams, the former circus strongman breached the walls of Khafre’s pyramid, only to find bovine bones within the sarcophagus – likely sacrificial offerings left by earlier intruders who had already absconded with the pharaoh’s remains.

The Tutankhamun Exception and Subsequent Discoveries

The long-sought breakthrough in finding an intact royal burial came in 1923 with Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. The boy-king, now arguably the most famous pharaoh, earned his renown from the astonishingly well-preserved treasures found within his burial chamber, including a solid gold sarcophagus and a golden death mask.

Unfortunately, Tutankhamun’s discovery shed no light on the pyramids, as his tomb was carved directly into the rocks of the Valley of the Kings, not housed within a pyramid. The ensuing “curse of the pharaohs” rumors, fueled by the deaths of several individuals associated with the excavation, added another layer of mystique to Egyptian archaeology, but did little to explain the empty pyramid sarcophagi.

Despite the setbacks, the quest continued. In 1925, near the base of the Great Pyramid of Khufu, American archaeologists led by George Andrew Reisner stumbled upon the tomb of Queen Hetepheres, Khufu’s mother. Although the burial chamber was remarkably well-hidden, her sarcophagus was also empty. It was only after overcoming their disappointment that the team discovered a hidden compartment containing the queen’s mummified viscera, leading Reisner to hypothesize that her body had been reburied elsewhere after an initial robbery.

Hope for an untouched pyramid burial rekindled in 1951 when Egyptian Egyptologist Zakaria Goneim unearthed a previously unknown pyramid at Saqqara. This unfinished structure, initially deemed insignificant, led Goneim through a series of elaborate tunnels and three stone walls. The discovery of jewelry inside fueled optimism that this might finally be an unlooted pharaoh’s tomb. However, upon opening the golden sarcophagus of Sekhemkhet, a little-known pharaoh, Goneim was met with the familiar sight of emptiness.

Beyond Tombs: Alternative Theories and the Evolution of Belief

The consistent failure to find pharaonic bodies within the pyramids has spurred numerous alternative theories. In the 19th century, Scottish astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth claimed the Great Pyramid was a scaled model of the Earth’s circumference, though his calculations were flawed due to debris obscuring the pyramid’s base. More recently, in 1974, physicist Kurt Mendelssohn proposed that the pyramids were massive public works projects designed to forge a national identity among disparate Egyptian tribes.

Another persistent issue for the tomb theory is the fact that several pharaohs constructed multiple burial sites. King Snefru, Khufu’s father, had three pyramids, making it unlikely he intended to divide his remains among them. Khufu himself had only one pyramid, but it contained three chambers seemingly designed as burial rooms.

Consequently, another theory gaining traction is that the pyramids served as memorial shrines. These would have been monuments honoring deceased pharaohs, with their actual burial places hidden elsewhere to protect them from looters. This would explain the abundant funerary features without the presence of bodies.

The Enduring Purpose: A Journey to the Afterlife

Despite these alternative explanations, the majority of Egyptologists continue to believe that the pyramids were fundamentally built as tombs, even if they served other purposes concurrently. They are surrounded by other tombs, albeit for less prominent dignitaries. Even if ancient and modern thieves looted every trace, the pharaohs’ bodies were once interred there.

From a scholarly perspective, the pyramids are best understood as part of an architectural progression that began with flat-topped, rectangular mud-brick tombs known as mastabas, where bodies were indeed found. Over time, architects began stacking mastabas, creating the stepped pyramids, the most famous of which stands at Saqqara. Eventually, this evolved into the familiar sloped sides of the true pyramid, perhaps first at Meidum.

This architectural evolution mirrored theological shifts. Early mastaba texts suggest a belief that pharaohs would ascend to the heavens via steps. Later texts from the true pyramid period reflect the growing cult of the sun god, describing pharaohs rising to the sky on the sun’s rays. The sloping sides of the pyramids, resembling sunbeams radiating from the sky, became the new pathway to the heavens.

Did the worship of the sun inspire the Egyptian architects to design the pyramids? While it might seem incredible to us today that such immense efforts were undertaken simply because a ladder was no longer deemed an effective means of reaching the afterlife, for the Egyptians, this endeavor was deeply meaningful. (It is also crucial to note that the pyramids were built by Egyptians, not enslaved Israelites, a common misconception.)

Almost everything remaining from ancient Egyptian civilization is tied to death. It appears to have been the defining force in their religious beliefs, literature, and art. For the pharaohs, the afterlife was a very real destination, whether by steps or sunbeams. Therefore, it is entirely fitting that the monumental structures defining their civilization for future generations were also, almost certainly, designed to house their deceased.