A Monument Shrouded in Mystery

The pyramids of Egypt, the Parthenon in Greece, the Roman Colosseum – all evoke images of grand civilizations, pharaohs and philosophers, emperors and epics. Stonehenge, however, stands apart. This massive stone ruin on Salisbury Plain is not surrounded by ancient cities but by modern highways leading to London. There are no hieroglyphs to decipher, no Socratic dialogues to interpret. The Stone Age and Bronze Age people who built Stonehenge also constructed smaller stone monuments, their ruins scattered across the countryside. Yet, they left no record explaining how or why they achieved such a singular and astonishing feat of engineering as Stonehenge. Until late in the 20th century, the ancient inhabitants of Salisbury Plain were considered so primitive that historians felt no compunction in describing them as “barbarians.”

Early Theories: Merlin, Romans, and Druids

It’s no surprise, then, that those who studied this ancient circle of stones, from the Middle Ages onward, looked beyond Salisbury Plain for its builders. In the 12th century, the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth attributed Stonehenge to Merlin, King Arthur’s court wizard. According to Geoffrey’s “History of the Kings of Britain,” Arthur’s uncle, Aurelius Ambrosius, ordered its construction to commemorate a great victory over Anglo-Saxon invaders. Merlin suggested transporting a circle of stones from a place called Killaraus in Ireland and arranged for the pre-fabricated monument to be moved across the sea to Britain.

In the 17th century, King James I was so captivated by Stonehenge that he commissioned his court architect, Inigo Jones, to investigate it. After studying the site, Jones agreed with Geoffrey of Monmouth: the Stone or Bronze Age inhabitants of the area likely couldn’t have built it. Jones reasoned, “If they wanted the knowledge to clothe themselves, they could have none to erect such stupendous buildings, or magnificent works as Stonehenge.” Jones concluded that “a building of such greatness” could only be the work of the Romans, likely a temple to an unknown Roman deity.

Subsequent years saw continuous efforts to attribute Stonehenge to builders from almost anywhere but Britain. Danes, Belgians, and Anglo-Saxons all had their proponents, as did the ancient Celtic priests known as Druids. The problem with all these theories was the same. Though radiocarbon dating wasn’t invented until the 20th century, simpler dating methods available to early archaeologists indicated Stonehenge was likely constructed before 1500 BC. Most researchers also knew that the Druids didn’t arrive until after 500 BC, and the Romans even later. This meant Stonehenge was built over a thousand years before either of them.

So, the question remained into the 20th century: Who built Stonehenge?

The Mycenaean Connection: A Promising but Flawed Theory

A serendipitous discovery by an archaeologist in 1953 hinted at a solution. On July 10th, as part of his survey of the site, Richard Atkinson was preparing to photograph some 17th-century graffiti on a stone next to what is known as the Great Trilithon. As he looked through his camera, Atkinson noticed other carvings beneath the 17th-century inscription. One was a dagger pointing downwards, and nearby, four axes of a type found in England around the time Stonehenge was built.

It was the dagger, not the axes, that most excited Atkinson. Nothing like it had been found in England or anywhere in Northern Europe. Its closest resemblance was to artifacts from the royal tombs of Mycenae in Greece. Here, finally, was a link to a more advanced civilization, one that could logically be expected to have built something like Stonehenge. Even better, daggers found in Mycenae dated to around 1500 BC, roughly the same time most 1950s experts believed Stonehenge was built. Unlike the Romans or the Druids, the Mycenaean connection had compelling chronological logic.

Atkinson developed a well-reasoned theory: Stonehenge was designed by a visiting architect from the more civilized and sophisticated Mediterranean. He even speculated that a Mycenaean prince might be buried on Salisbury Plain. The archaeological world, relieved to finally have an answer to the Stonehenge puzzle, largely accepted this theory.

Radiocarbon Dating and a Local Origin

But just as quickly as consensus formed around the Mycenaean connection, it crumbled. The 1960s brought a new form of radiocarbon dating, and suddenly archaeologists faced strong evidence that Stonehenge was much older than previously thought, and far older than the Mycenaean civilization. The new radiocarbon dates confirmed that the citadel at Mycenae was built between 1600 and 1500 BC, but they pushed the origins of Stonehenge back even further, before any Mediterranean influences could have been felt.

With this new estimation, the construction of Stonehenge’s outer ditch and bank began around 2950 BC. Wooden structures were added within the circle between 2900 and 2400 BC, to be replaced by the familiar stone construction shortly after.

The new dates not only undermined the Mycenaean theory but also the entire “diffusionist” mindset that had driven it. Stonehenge was simply too old to have been built by any of the great European civilizations, and non-European civilizations were too distant. For the first time, most researchers had to accept that the builders of Stonehenge were people who lived near Stonehenge, and they did it without outside help. These seemingly primitive people had, somehow, built one of the world’s most enduring monuments.

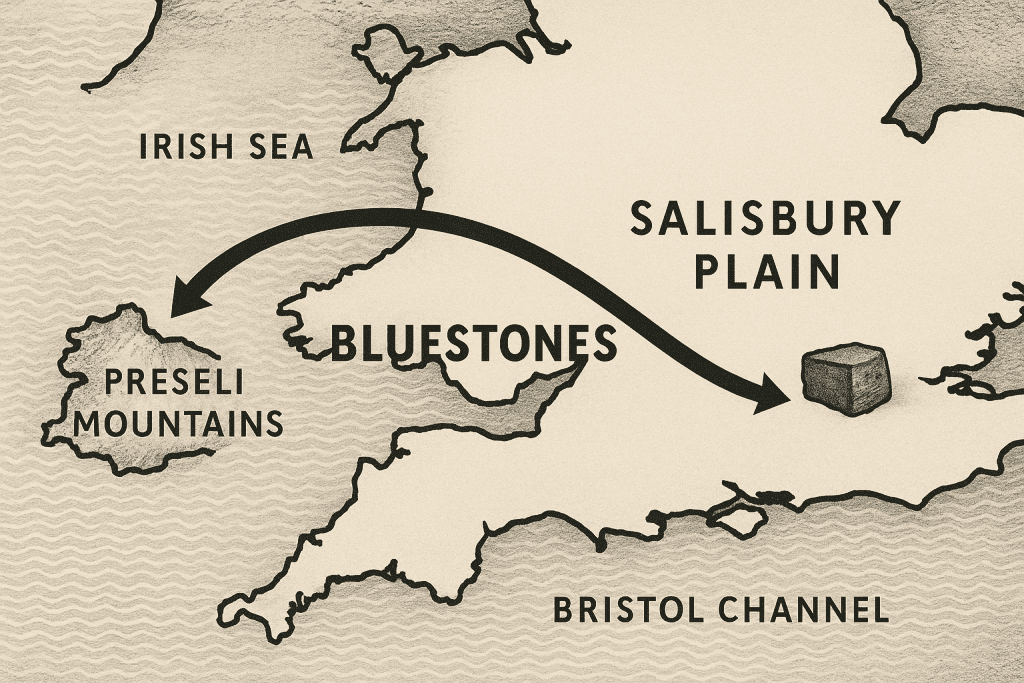

The Mystery of the Bluestones

What’s more, the builders of Stonehenge made their task astonishingly more difficult – as if what came before wasn’t impressive enough – by using stones brought from 150 miles away, from the Preseli Mountains in southwest Wales. These “bluestones” (which were actually more of a mottled gray) were traced to their source by geologist H.H. Thomas in 1932. He found that the three rock types in the bluestones were unlike any found near Stonehenge. However, Thomas discovered the same three rocks could have been quarried from natural outcrops between the peaks of Carn Menyn and Foel Trigarn in Wales.

But how did the people of Salisbury Plain transport these stones, some weighing five tons, from Wales to England?

Thomas’s discovery led some to revisit Geoffrey of Monmouth’s story of Merlin’s magic. Archaeologist Stuart Piggott suggested there might have been some genuine oral traditions embedded in the folklore. After all, Geoffrey had written about Merlin obtaining the stones from the west (albeit Ireland, not Wales) and about them being transported to Stonehenge by sea, which might have resonated with a folk memory of transport across the Irish Sea. Geoffrey might even have offered a hint as to why Stonehenge’s builders went to such lengths to bring stones from afar when plenty of other rock types were available right around Salisbury Plain: perhaps, like Merlin in Geoffrey’s story, the builders of Stonehenge believed these rocks had magical properties.

Most historians found Piggott’s suggestions a bit far-fetched, especially given Geoffrey’s distorted historical account. But it still didn’t answer how at least eighty-five stones—and possibly more—traveled from the Preseli Mountains to Salisbury Plain.

Some, most notably geologist G.A. Kellaway, argued that the bluestones were carried by glaciers, not by people. But most experts stood united against him, not believing that the most recent glacial coverage extended as far south as Preseli or Salisbury. Even if it had, and ice extended to both locations, it’s highly improbable that glaciers would have collected bluestones from one small area in Wales and deposited them in another small area in England, rather than scattering them everywhere. The absence of other bluestones in South or East of the Bristol Channel (with the possible exception of one now in Salisbury Museum, but its dating remains controversial) has provided a strong argument against the glacial theory.

Thus, the most accepted explanation, once dismissed, was that the inhabitants of the Salisbury Plain region lashed together boats and carried the bluestones across the Irish Sea. The journey served as further evidence that the people of Salisbury Plain possessed astonishing and unusual technical expertise.

Stonehenge as an Astronomical Observatory

Amidst the confusion of diffusionist proponents, the 1960s saw more remarkable claims made on behalf of the Salisbury Plain people. This time, they came not from archaeologists or geologists, but from astronomers.

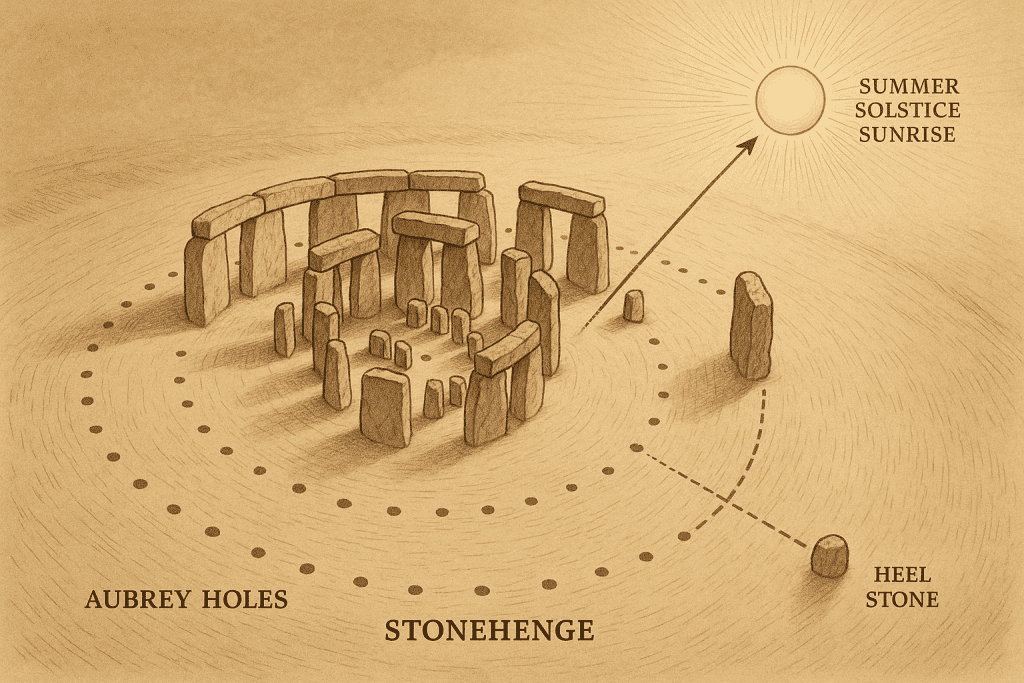

The 1960s weren’t the first time astronomy entered the picture. As early as the 18th century, William Stukeley observed that Stonehenge’s center lay “nearly where the sun rises, when the days are longest.” Many others who studied the monument found other alignments pointing to the sun, moon, or stars. However, none of these studies created a stir quite like that by Boston University astronomer Gerald Hawkins, whose confidently titled book, “Stonehenge Decoded,” became an international bestseller in 1965.

Hawkins found that the alignment between 165 key points in the monument correlated strongly with the positions of the rising and setting sun and the appearance and disappearance of the moon. More controversially, he argued that a circle of holes at Stonehenge known as “Aubrey Holes” was used to predict lunar eclipses, leading Hawkins to dub Stonehenge a “Neolithic computer.”

Atkinson, still the leading authority on Stonehenge since his discovery of the “Mycenaean” carvings, responded with an equally scathing article titled “Moonshine on Stonehenge.” Atkinson argued that the celestial alignments could very well be coincidental. As for the Aubrey Holes as eclipse predictors, Atkinson pointed out they were used as cremation pits and were quickly filled after being dug.

The ensuing debate largely pitted astronomers against archaeologists, with practitioners of each field perpetually struggling to understand the other’s technical arguments. Astronomers came up with a host of other ways Stonehenge could have been used as an astronomical observatory, some of which were less easily dismissed than Hawkins’s methods. But astronomers had a tendency to emphasize how different points aligned with the sun or moon while ignoring that one of these supposed alignment points might have been built hundreds or even a thousand years after another. Archaeologists were quick to find flaws in most of these theories.

An Enduring Legacy of Ingenuity

By the end of the second millennium, though the debate continued, there were signs of a growing consensus. The wilder theories, like Hawkins’s, were discredited, even among astronomers. Yet, almost all archaeologists (including Atkinson) acknowledged that at least a few of the celestial alignments, especially with the sun, were more than mere coincidence. Most likely and widely agreed upon, the monument was not used as an observatory, at least in the modern sense. However, the people of the Stonehenge area likely observed the sun from there, perhaps as part of a prehistoric ritual.

Even this imprecise astronomical knowledge indicated that the people of Salisbury Plain had studied the sky and had some system for tracking their observations. Clearly, the builders of Stonehenge, however primitive in some ways, were remarkably sophisticated in others. In this regard, the latest discoveries have further deepened our understanding while simultaneously increasing the mystery surrounding Stonehenge’s builders.